The „о–¬–”∞…‘≠іі region has been stuck with nuclear waste ever since it helped give the United States the atomic bomb in the 1940s. But concern about the risks of radioactive contamination has spiked recently.

Activists and residents who live near contaminated sites, especially in north „о–¬–”∞…‘≠іі County, have pressed for of their homes and for damages. TheyвАЩve protested on street corners and angrily confronted government officials at stormy public meetings. School leaders have sent warning letters to parents; s with their children.

People are also reading…

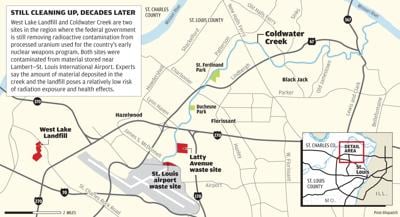

Much of the new awareness of the regionвАЩs nuclear legacy can be attributed to a slow-burning underground trash fire in a Bridgeton dump that drew attention to the adjacent West Lake Landfill, where .

But other contaminated sites have grown in notoriety, too. A citizens group has raised the profile of , a tributary of the Missouri River that meanders across north „о–¬–”∞…‘≠іі County. TheyвАЩve used and tallied cancers among people who grew up near the waterway.

Fear, fueled by the popular perception of radiation risks and the slow response to the fire by landfill operator Republic Services and the EnvironmentalћэProtection Agency, has stoked conflict and distrust.

Environmental Managers Erin Fanning (left) and Brian Power stand at a low fill area where a subsurface reaction has already taken place at the Bridgeton Landfill on Friday, May 13, 2016. Photo by Cristina M. Fletes, cfletes@post-dispatch.com

But that fear may be overblown and even misplaced, say experts on radiation who have reviewed radiation measurements at the sites and were interviewed by the Post-Dispatch.

The waste emits only tiny amounts of the gamma rays that can penetrate all but the most dense material, including the human body. Instead, almost all of the radiation released by the waste comes in the form of alpha particles, radiation that canвАЩt pierce the skin and needs to get inside the body to do damage.

Asked to review measurements of radionuclides in the West Lake Landfill and Coldwater Creek gathered by regulators, Sasa Mutic, the director of radiation oncology physics at Washington University School of Medicine, indicated the risks from exposure are akin to driving a car.

вАЬAll of this would be well within what we give people for medical procedures,вАЭ Mutic said. вАЬAt this level, there are many other things that are much riskier.вАЭ

After years of testing, the highest concentration of contamination the EPA has detected near the surface of West Lake would require ingesting over an ounce to deliver the same radiation dose as a whole-body CT scan, according to dose calculations from the and reviewed by experts. The dose from a whole-body CT scan, according to the National Research Council, a nonprofit institution that produces reports reflecting the scientific communityвАЩs views, would be .

The council puts the lifetime cancer risk from all sources at 42 in 100.

But the highest radionuclide concentrations in West Lake are not the norm, and many of the higher readings are dozens of feet underground. With most dirt at West Lake, it would take ingesting at least a quarter-pound, if not more, to deliver a CT scanвАЩs worth of radiation, according to EPA estimates of average concentrations.

The highest concentrations arenвАЩt even in the portion of West Lake closest to the underground Bridgeton Landfill fire. TheyвАЩre across a service road, separated from the burning landfill.

Still, Ed Smith, who follows nuclear waste for the Missouri Coalition for the Environment, says the risk is too great that contaminants will someday be spread into the community. The nearby Missouri River could overtop levees, a tornado could blow through or the Bridgeton Landfill fire could reach West Lake. And unlike medical procedures, living next to a radiation source is not a choice residents knew they were making, he said.

вАЬThere are two ways radioactivity is going to be removed from this site: through planned removal or Mother Nature,вАЭ Smith said.

The EPA looked at the risk to on-site or nearby workers, assuming nothing is ever done to cap the site or remove the radioactive waste. Those hypothetical workers would spend a lifetime close to the waste, вАЬwhich I would say is a much stronger driver of risk,вАЭ said Tom Mahler, a nuclear engineer with the EPAвАЩs Superfund program. A disaster could move waste off site, but it would be cleaned up and people wouldnвАЩt spend year after year working near it, he said.

A water truck performs dust suppression as part of the non-combustible cover project at the OU-1 Area 2 of the Bridgeton Landfill on Friday, May 13, 2016. The area contains radiological impacted materials (RIM) at or near surface level and is being cleared of trees, then covered with geotextile and gravel to mitigate fire potential. Photo by Cristina M. Fletes, cfletes@post-dispatch.com

While the EPA has ordered more work to try to keep the Bridgeton Landfill fire from ever reaching West Lake, Mahler said he believes вАЬitвАЩs extremely unlikely that something would move off site even if that event would occur.вАЭ

If the fire does reach the landfill, EPA sees a bigger risk to on-site workers from radon exposure, produced as the uranium processing waste decays. Even then, itвАЩs not as dangerous as indoor radon exposure.

вАЬAssuming weвАЩre not growing plants out of it, I would say the main problem is the radon escaping out of the soil,вАЭ said David Simpson, a health physicist and professor at Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania. вАЬThe dilution factor when it decays out into the open is going to be tremendous. What you donвАЩt want to do is build a house over it.вАЭ

The levels of contamination are far higher than EPA regulations allow, but experts say those regulations are conservative, with levels set low enough to allow for future residential use.

вАЬThe only way theyвАЩd be dangerous to a person is if they were somehow ingested in large quantities,вАЭ Mary Lou Dunzik-Gougar, an associate professor of nuclear engineering and a research scientist at the Idaho National Laboratory, said in an email after reviewing West Lake radionuclide measurements. вАЬSo, the question is whether or not these radionuclides could somehow get into the water or air and then be ingested to a large extent, which is unlikely because youвАЩd need to ingest quite a lot. ItвАЩs really a matter of cleanup to meet regulatory requirements.вАЭ

'Well-understood' risk

Radiation is among the easiest carcinogens to detect, scientists say.

вАЬThere is nothing you can measure as easily as a radioactive contaminant,вАЭ said Dr. Henry Royal, associate director of nuclear medicine at Washington University School of Medicine. вАЬItвАЩs both a blessing and a curse.вАЭ

He calls radiation a вАЬrelatively weakвАЭ carcinogen compared to other chemicals. The fear it induces is often more damaging.

Jamie Bushman, a radiation protection superior, holds a radiation detector he uses to test soil being dug out of a trench along Frost Drive in Berkeley on Tuesday, April 12, 2016. The street where the trench is being dug is in an area of concern inside the record of decision boundary, so anytime the soil in the area is disturbed the process needs to be monitored and radiation tests taken to ensure contaminated soil is not spread around. Photo by David Carson, dcarson@post-dispatch.com

вАЬIn any event involving radiation, the biggest effect that we can measure is the psychosocial effects,вАЭ said Royal, who studied health effects from Chernobyl, the 1986 nuclear plant accident, for the International Atomic Energy Agency.

ThatвАЩs not to say radiation doesnвАЩt cause cancer вАФ it does. But the risk is lower than most people think.

вАЬThereвАЩs no threshold for radiation effects,вАЭ Mutic said. вАЬSome radiation effects will happen at very low levels, but the likelihood of those happening areћэextremely low.вАЭ

Much of the basis for our knowledge of radiation effects comes from studying survivors of the atomic bombs the U.S. dropped in 1945 on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan.

Continuing indicate the number of cancers due to radiation made up about 11 percent of the total number of cancers. , including cardiovascular disease and immune system deterioration, were also observed. cases nearly doubled, although only 204 of more than 49,000 survivors were diagnosed with it.

Radiation doses are usually expressed in millirem or millisieverts. The average American typically of natural radiation, or 3.2 millisieverts, annually.

The atomic bomb survivors, on average, received about 120 millisieverts of radiation, or 12,000 millirem, Royal said. ThatвАЩs about 12 CT scans all at once.

Natural radiation doses change depending on where you live. Brick homes emit more radiation, and in Denver, people receive about 50 more millirem of cosmic radiation per year than people who live at sea level.

Higher cancer rates, however, are hard to detect.

вАЬThereвАЩs so many other compounding factors that you really canвАЩt come up with good statistics for it,вАЭ said Simpson, the health physicist. вАЬThe risk is small enough that itвАЩs really lost down in the statistics.вАЭ

The National Research CouncilвАЩs estimates that one person in 1,000 would be expected to develop cancer if he or she were exposed to an additional 1,000 millirem, or 10 millisieverts, of radiation, about as much as a whole-body CT scan.

At the West Lake Landfill and Coldwater Creek, the contaminants are made up of uranium decay products: thorium and radium mostly, which decay into shorter-lived radon and other elements.

The concentrations of those materials in the West Lake Landfill are measured in picocuries. When doctors use radioactive elements in tests or treatment, вАЬthe unit we use is millicuries,вАЭ Royal said. Even the most contaminated portions near the surface of West Lake contain only about 30,000 picocuries per gram of thorium, or 0.00003 millicuries. The concentrations of radium and uranium are lower still.

вАЬWeвАЩre talking about really, really small amounts of radioactive material,вАЭ Royal said.

Coldwater Creek

If what is in theћэWest Lake Landfill is small, what now remains in Coldwater Creek and is smaller.

The highest concentrations the Army Corps of Engineers has located are on the properties near Lambert-„о–¬–”∞…‘≠іі International Airport and Latty Avenue that served as the original storage location for the regionвАЩs radioactive waste. The most the corps has found is about 38,000 picocuries per gram of radioactive thorium.

Coldwater creek radiation

Those original storage locations have been cleaned up, but a private research organization says it recently found a spot that contains about 11,000 picocuries per gram of radioactive thorium.

The corps says it was aware of that spot but that itвАЩs inaccessible; the public would have to dig underneath railroad tracks to get to it.

Even the highest current levels of radioactive contamination, however, shouldnвАЩt cause too much concern, said Jonathan Rankins, a health physicist for the corpsвАЩ Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program, or .

вАЬItвАЩs still an extremely small number,вАЭ Rankins said. вАЬYouвАЩd still need to spend some time there or eat a lot of vegetation.вАЭ

He added: вАЬThereвАЩs nothing even close to that in the creek or along the creek.вАЭ

Still, the corps is meticulously measuring and removing dirt along the creek, including the , to cut levels down to 5 picocuries per gram on the surface and 15 picocuries per gram below the surface.

FUSRAPвАЩs cleanup goals are based on a 40-year-old uranium mill tailings cleanup law, not вАЬa modern-day cancer risk assessment,вАЭ Rankins said.

In other words, the cleanup standards require remediation even at levels that Rankins says are not dangerous. PeopleвАЩs perceptions of the risk, he worries, are doing more damage than the contamination could.

Regina Engelken, who lives in Richmond Heights but grew up in Coldwater Creek, watches a slide presentation on Thursday, Oct. 15, 2015, of the Attorney General's assessment of the landfill and nuclear waste situation at the Bridgeton Republic Services dump at a meeting by Just Moms at John Calvin Presbyterian Church. Photo by Christian Gooden, cgooden@post-dispatch.com

вАЬI worry the stress that this has caused is doing more harm than good,вАЭ he said. вАЬI donвАЩt want to be an alarmist that causes other unintended consequences.вАЭ

The past is a different story, Rankins admits. No one knows what the levels in Coldwater Creek were 60 years ago, when the north „о–¬–”∞…‘≠іі County suburbs were developing along the waterway while radionuclides leached into it from the storage sites near the airport. Radionuclide levels in the creek likely peaked between 1950 and 1965, he said, and people could have been exposed.

The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry is investigating the historic contamination levels, and any health problems they may have caused.

вАЬThey historically were higher,вАЭ Rankins said. вАЬThey just have been washed out over time.вАЭ

Exposure pathway

ThereвАЩs far less, if any, evidence of direct radiation exposure from West Lake, which is fenced off and intensely monitored.

ItвАЩs not for lack of trying. Scientists whose studies have been funded by environmental activist Kay Drey around the perimeter of the landfill but have been unable to find anything much higher than background. The Missouri Department of Natural Resources releases reports and hasnвАЩt reported detectable radiation, picked up radiation off site.

The smoldering Bridgeton Landfill, on the other hand, into the air, although they werenвАЩt radioactive. Air monitoring has shown levels of benzene, sulfur dioxide and hydrogen sulfide have at times exceeded regulatory guidelines. Readings below regulatory levels of concern since 2013, after Republic Services installed equipment to flare off gasses and .

Workers lay down geotextile at the Bridgeton Landfill as part of the non-combustible cover project at the OU-1 Area 2 of the Bridgeton Landfill on Friday, May 13, 2016. The area contains radiological impacted materials (RIM) at or near surface level and is being cleared of trees, then covered with the geotextile and then gravel to mitigate fire potential. Photo by Cristina M. Fletes, cfletes@post-dispatch.com

Missouri Attorney General Chris KosterвАЩs office released studies last year indicating offsite trees absorbed radioactive material from the landfill. But the studies only indicated some trees had higher than background levels and didnвАЩt quantify by how much. The and dismissed the studies.

beneath the landfill, but the levels are low enough that someone would have to drink more than 1,000 gallons to be exposed to as much radiation as the average American gets annually from radon.

Along Coldwater Creek, which passes through residential neighborhoods in St. Ann, Florissant and Hazelwood, some former residents have documented what they believe is a pattern in the incidence of cancer among those who grew up in the area. The Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services added validity to some of those theories with in the ZIP codes around Coldwater Creek and the West Lake Landfill.

Dr. Adetunji Toriola, a cancer researcher at Washington University, said higher rates of leukemia warrant further research, but itвАЩs too early to say what is causing the cancer or whether there is a cancer cluster вАФ a statistically higher level of cancers caused by an environmental contaminant.

Many have pointed to a number of reported cases of rare appendix cancer, but those didnвАЩt show up in the state data. Some argue those data donвАЩt include people who grew up and moved away.

Toriola said bone and thyroid cancers, in addition to leukemia, would be expected due to radiation exposure. But bone and thyroid cancers werenвАЩt statistically higher, and appendix cancer вАЬis not a typical radiation-related cancer,вАЭ he said.

However, high rates of other risk factors associated with cancer вАФ obesity, smoking, poor diets or exposure to other chemicals вАФ can increase cancer risk from radiation exposure, Toriola said. вАЬThe level that is required to cause cancer may be lower than in an otherwise healthy individual.вАЭ

'The first bogeyman'

Soil with low-level radioactive contamination sits in a pile at „о–¬–”∞…‘≠іі Airport Storage Site on Tuesday, April 12, 2016.

A paper published in the medical journal Clinical Oncology recently pondered how the вАЬscientific facts around the real risksвАЭ of low-dose radiation became вАЬoccluded by science fiction.вАЭ

вАЬWe have 70 years of data from the atomic bomb cohorts and 30 years of data from Chernobyl,вАЭ wrote the authors, Paul Symonds, a cancer researcher at the University of Leicester, and Geraldine Thomas of the department of surgery and cancer at Imperial College London. вАЬSurely we should now be able to interpret that data with enough confidence to say that the popular beliefs around radiation risk are incorrect вАФ the scientific data tell a totally different story.вАЭ

David Ropeik, who consulted for the EPA at West Lake on risk perception and is an instructor at the Harvard Extension school, said peopleвАЩs fear of radiation is deeply rooted.

вАЬRadiation was the first bogeyman for modern environmentalism,вАЭ he said. вАЬWe were all freaked by the bomb and the testing and the вАШGodzillaвАЩ movies. ItвАЩs burned into our brains.вАЭ

But inflating the risk of radiation can actually lead to poor health outcomes, Royal warned.

вАЬIt makes people focus on that as the cause of any of their illnesses,вАЭ he said. вАЬAnd one of the things that hopefully sounds logical is that in order to truly treat an illness you have to treat the true cause of it.вАЭ

Helping families reduce radon buildup in their homes would cut radiation exposure on a much wider scale, Royal said. The EPA estimates lung cancer from naturally occurring radon in basements kills 20,000 people each year.

вАЬIf the goal was to protect people from small radiation doses, we could do it much more responsibly and much more effectively by sponsoring radon-mitigation programs in peopleвАЩs homes,вАЭ Royal said.

In this Series

„о–¬–”∞…‘≠іівАЩ long history of radioactive contamination. Highlights of 10 years of Post-Dispatch coverage.

-

Feds want to test for nuclear waste near Coldwater Creek at „о–¬–”∞…‘≠іі County park

-

House committee hears testimony on compensation for „о–¬–”∞…‘≠іі-area residents exposed to radioactive waste

-

Missouri lawmakers seek federal compensation for radioactive contamination in „о–¬–”∞…‘≠іі region

- 55 updates