The 2,200 transfer students have fanned out across the �����Ӱ�ԭ�� region in search of a better education than they were getting in the troubled Normandy and Riverview Gardens school districts.

And where they have gone, tuition money has followed.

So far, school systems that have enrolled the students have billed Normandy and Riverview Gardens more than $9 million, hurting the two districts’ budgets in the process. Annual tuition payments paid on behalf of the students can reach $20,000 per child, with districts determining the amounts using a loosely defined formula in the state law.

Yet large portions of that money has not been exclusively set aside for the education of those students, particularly those who struggle academically.

A Post-Dispatch inquiry has found that in some districts, tuition payments have instead been absorbed into districtwide budgets. And while other districts have hired additional instructors and support staff, large amounts of the tuition payments remain unspent in school district bank accounts.

People are also reading…

There’s little dispute that transfer students have created new financial burdens for the districts now paid to serve them. Like all students, they require art supplies, desks, textbooks and even paper towels.

But with few exceptions, the new students have been absorbed into existing schools without the need of more teachers and new classrooms.

The paradox has led to a larger conversation in the region and in Jefferson City about whether a limit should be placed on the amount school districts charge for tuition.

“What do they really need to do to support these kids?” said Carole Basile, dean of the College of Education at the University of Missouri-�����Ӱ�ԭ��. “That’s the real question.”

That debate is building as the tuition payments continue to cripple the unaccredited Normandy and Riverview Gardens districts. Without an influx of cash, Normandy could go bankrupt this spring.

Now, some superintendents in the receiving districts are questioning whether they should return part of the money to Normandy to stave off its collapse.

In 11 districts that have received 90 percent of the cash from the transfer program, fewer than half of them have added teachers and staff as the result of the influx of transfer students.

One district — Ferguson-Florissant — hired 10 new teachers directly resulting from the 440 transfer students enrolled there.

Another three districts — Francis Howell, Pattonville and Clayton — have dipped into their tuition payments to add support staff such as reading specialists, teachers aides, substitute teachers or after-school supervisors. Mehlville and Kirkwood have budgeted some tuition revenue for after-school activity buses.

Hazelwood and Ritenour officials say they’re using the payments for general education instruction and programming.

While Kirkwood, Mehlville and Ladue have added teachers this year, it was in response to overall district growth and not a direct result of transfer students, officials there say.

“Of the money that we have, the majority of it we haven’t spent. We’ve put it aside,” said Susan Dielmann, communications director for the Ladue School District. “We didn’t want to count on that money. We didn’t know how this would play out.”

Only University City officials did not provide answers to questions concerning the $340,000 that the district has so far received.

AN UNCERTAIN SITUATION

Last summer, the Missouri Supreme Court upheld a law that allows children in unaccredited districts to transfer to better schools at their home district’s expense. The ruling led to an unprecedented migration of students from two north �����Ӱ�ԭ�� County school districts into 23 higher-performing school systems across the region.

The transfer law clearly gives failing districts the responsibility of paying tuition and transportation costs for students who transfer under the statute. But it is silent in how receiving school districts spend the money.

For the most part, transfer students have been widely dispersed, with no more than a small handful in any one elementary school classroom, for example.

The Missouri education department advised districts last summer to turn transfer children away once class size limits had been met. That ability to cap class sizes has alleviated the need to hire dozens of teachers, even in districts that have accepted hundreds of transfer students.

Last summer, many school officials expressed reluctance to commit tuition funds to staff salaries, in the event either unaccredited district failed to pay tuition bills.

While the bills have been paid on time, no one is sure how long tuition payments will continue. The cost to Normandy and Riverview Gardens is expected to be about $30 million this year. In October, the Normandy School Board voted against paying tuition bills after authorizing the closure of an elementary school and 103 layoffs to offset transfer costs. The board later reversed its decision, but concerns remain.

“We’ve received $640,000. I don’t know if we’ll get another penny,” Mehlville Superintendent Eric Knost said. “It’s dangerous for me to make decisions, long-term contracted decisions, based solely on the dependency of this money. That’s just not sound decision-making.”

Mark Stockwell, chief financial officer for the Parkway schools, said his district also has not spent the bulk of its tuition money for similar reasons.

SUPPORTING STUDENTS

But amid the funding debate, parents in the transfer program say they’re happy with the attention their children are getting in their new classrooms.

“I’ve only heard good things about the plethora of services that they didn’t have back at the home districts,” said Amanda Schneider, staff attorney at Legal Services of Eastern Missouri, whose clients include families who left Normandy and Riverview Gardens.

Carmen Summers, whose son, Jayden, transferred to Kirkwood from Riverview Gardens, says she believes he has benefited from every advantage afforded to children within the district.

“He’s able to come home and explain his homework assignments,” Summers said. “I see a big difference. It’s been beneficial.”

The academic skills of transfer children span the spectrum.

That’s true at Oakville Middle School in Mehlville, where a transfer student is part of the gifted program. For those who are behind academically, the school is able to meet their needs just as it does resident children — using existing staff.

“Some have challenges,” Principal Mike Salsman said. “We address those challenges throughout the day.”

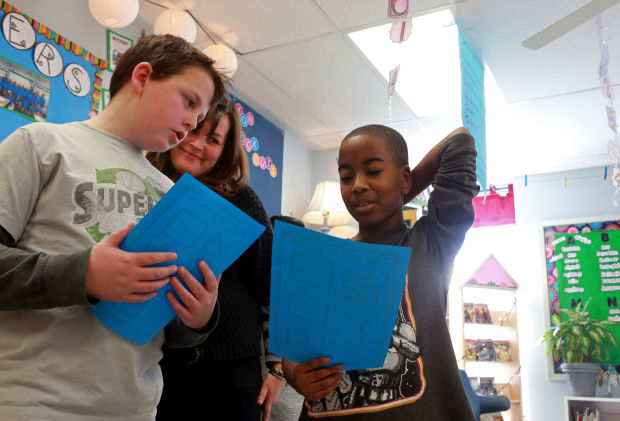

At Rose Acres Elementary School, which has the most transfer students within the Pattonville district, two staff were hired with tuition revenue for the benefit of the 26 transfer students.

In four months, Nancy Stevens-Martin has helped third-graders who hadn’t mastered their multiplication tables by putting them to song. She’s worked with children having trouble counting coins. She’s helped pupils struggling to read paragraphs.

“I’ve been paid to come here because they’re here,” said Stevens-Martin, a reading and math specialist. “It feels gratifying.”

Among the transfer students making gains is Orney Walker IV, a fourth-grader who just landed the starring role in the school musical. He started the year reading picture books. Now he’s choosing chapter books like Encyclopedia Brown at the school library.

Ron Orr, Pattonville’s chief financial officer said his district tracks every dime collected in tuition. Support staff has been added throughout the district to help transfer students academically. With the money comes responsibility, he said.

“As those resources are coming to us, we’re developing a plan to support those students the best we can,” he said.

Like Pattonville, Francis Howell hired support staff to meet the needs of transfer students. In some middle and high school courses, sections were added because of course requests. The district has also added supervision for those waiting bus pickups, as well as after-school snacks.

Kirkwood is paying for activity buses so the children from Riverview Gardens can participate in after-school activities.

“It’s the right thing to do,” Superintendent Tom Williams said.

Ferguson-Florissant hired 10 teachers in the fall because class sizes were going to be too large due to the influx of transfer students, School Board President Paul Morris said. But the nearly $4 million in tuition this year also could help the district erase its own budget deficit.

One school district, �����Ӱ�ԭ�� Public Schools, is waiting until the end of the school year — if at all — to bill for the 27 transfer students who have attended its schools, a district spokesman said. Just two years ago, when the city district was unaccredited, school system attorneys argued that the potential transfer of tens of thousands of children would quickly lead to bankruptcy.

SETTING LIMITS

As the tuition payments cut deeper into Normandy’s dwindling reserves, some are asking whether the tuition being charged by receiving districts is too steep.

In some cases, Normandy and Riverview Gardens are paying more in per-pupil tuition than they are receiving in per-pupil revenue. It’s why the two districts have 30 percent less money, but 20 percent fewer students. At the same time, there’s increased pressure on them to improve.

Educators throughout the region are aware of the problem.

“To have this amount of funding come out of these districts that are already struggling just doesn’t make any sense,” said Dielmann of Ladue. “We’re not going to decline the funding, but it is not an ideal situation.”

Some argue that without a cap of tuition, the situation is unsustainable.

“We saw with Wellston exactly what happens with what’s in place,” said Chris Tennill, Clayton schools spokesman, referring to the failing district just outside �����Ӱ�ԭ�� that folded in 2010. When about 100 of the district’s students transferred, Wellston struggled to pay the bills. Ultimately, the state dissolved the district and sent its students to Normandy.

“The law as it stands right now is forcing these unaccredited districts to hemorrhage money,” Tennill said.

Others say such a cap could create an economic burden on district taxpayers to support children beyond their borders.

“Why would a nonresident, a nontaxpayer, be entitled to a better price for the same quality of education?” said Kevin Supple, chief financial officer of Francis Howell, which stands to receive $3.4 million from Normandy this year.

Sustaining Normandy

��

Superintendents in the region are talking about April 1 — the potential date when Normandy could become insolvent. A request for $5 million in state funds to keep its doors open through the last day of school appears to have little traction in Jefferson City.

Normandy School Board member Terry Artis regularly votes against making the payments. He has watched as transfer tuition has almost destroyed the district’s once-healthy fund balance.

“All of it to me is an affront to the taxpayers of the Normandy School District,” he said. “Whether people have spent it or not is incidental. Us paying money to another school district is egregious.”

A Normandy bankruptcy would trigger the immediate dislocation of its 3,000 children. Some of those students could land in school districts that are receiving transfer students and their tuition.

As a result, a few superintendents are talking about the possibility of returning some of the tuition money to keep Normandy afloat. Such action would require approval from their school boards.

“You’re forced in a situation where you look at the lesser of two evils,” said Knost, the Mehlville superintendent.

Someone, he said, has to step up to keep Normandy schools open, if only for the rest of the school year.

“Just dissolving everything in front of kids’ eyes, there’s nothing child centered about allowing that to happen,” he said.

Walker Moskop of the Post-Dispatch contributed to this report