ST. LOUIS • It was an elegant evening at a downtown banquet hall, the tables served up with wine, grilled chicken and pesto mashed potatoes.

Donors, in their best suits and dresses, made offerings to Lydia's House, a nonprofit that helps abused women and children.

Some donated $3,000 for rent, others $2,000 for a year of child care or $100 for a community meal. A rowdy group bid $1,000 to have a young couple serve them drinks for the evening.

The fundraiser on a recent Saturday at the Westin Hotel, held at a stressful time for social service organizations, was a celebrated but serious moment. It garnered $85,000.

Still, no one could rival the generosity of Clara Schallert, who wouldn't have fit in at any of the banquet tables.

When she was alive, Schallert donned sweatshirts in the summer and jeans with secret pockets sewn inside. Hunched over, she walked at a fast clip and crossed the street to avoid men. A thick stocking cap hid her face.

People are also reading…

She was known as a hoarder and recluse in south ×îÐÂÐÓ°ÉÔ´´ — people called her a bag lady.

But she was also sitting on a $2 million fortune. And after her death, she left behind $200,000 that went to Lydia's House and another $200,000 to Gateway Homeless Services.

Today, two years after the gifts, the charities are still relying on the money in an era of economic struggle, budget cuts and increasing demand.

"We are fortunate to have some wonderful major donors, but to have a gift of that size appear at one time is not normal business for us," said Ellen Reed, head of Lydia's House.

The money helped pay down part of an expansion of apartments; it also filled a gap in Gateway's $1 million budget.

"Gateway is still using the money she left," said Mike Stokes, a board member. "It came at a difficult time for us."

Some knew Schallert was a shrewd businesswoman, but the extent of her holdings was a surprise to many. She was obsessively private and frugal, said relatives and neighbors.

"It was amazing that she was able to keep track of anything," said John Dachs, a nephew from Fenton and personal representative of her estate. "Her life was in disarray. Yet in seeing what she accomplished, that makes it even more amazing."

After she died at age 75, she left an entanglement of land and money that would take years to untie. But one demand was clear: She wanted the bulk of her money to provide a safe home for women.

EARELY LIFE ON A FARMÌý

Born in 1928, Clara E. Schallert grew up with six siblings on a southeastern Missouri farm near Portageville, north of the

Arkansas border. She was expected to milk cows before and after school.

A black-and-white photograph taken in the late 1940s shows her as an attractive young nursing student leaning into the field of a camera lens, smiling, which was a rarity decades later; a hat barely rests atop thick curly hair that spills to her shoulders.

She went on to work in a ×îÐÂÐÓ°ÉÔ´´ psychiatric ward, which used to give her nightmares, a family member said. She traveled to various states as a private nurse. For a spell, she lived in a convent.

Slowly, she became reclusive.

"Her personality and mind didn't go along very well," said a brother, Bernard Schallert, 80, of Effingham, Ill. "It got worse and worse and worse."

By the 1960s, she settled in south ×îÐÂÐÓ°ÉÔ´´ with her sister Marie, who also neither married nor owned a car. They lived in a small brick home on Milentz Avenue, nearly at the foot of Our Lady of Sorrows Catholic Church, which they attended regularly.

Neighbors remember Marie, who worked as an auditor in a downtown bank, as friendly. Clara was the evasive one, the collector of anything she thought would hold value.

"You'd always see her carrying stuff that she found — newspapers, plastic cottage cheese containers," said Bob Bayer, who grew up on the block and still lives there. "Anything you can imagine, she didn't get rid of it and brought it home."

The Schallert sisters became fixtures in the neighborhood. They canned fruits and vegetables. They attended family reunions in Portageville. And they quietly invested in property together.

MOVING AHEADÌýALONE

The companionship ended in a tragic accident in 1989, when a pickup slipped out of park and ran over Marie on a Belleville sidewalk. Clara inherited Marie's estate and became even more isolated.

She started renting apartment space to live in and store stuff. She accumulated so much in one that she was asked to move out.

She also became a regular at the ×îÐÂÐÓ°ÉÔ´´ Circuit Court, especially in squabbles over Marie's estate. She took on the truck owner's insurance company. She pursued legal action against her family members. She fought over a home she wanted to acquire on Louisiana Avenue in the city.

She often represented herself, saying she couldn't afford an attorney. She frustrated lawyers, judges and at least one bailiff, who pleaded during a hearing: "Ma'am, you and I have been going around and around downstairs since you've been coming in this building. Just answer the gentleman's questions."

Schallert also bought rental homes in downtown Portageville, where, in addition to property passed down from her father, she acquired more farmland.

In one transaction in southeastern Missouri, a seller wouldn't accept a personal check. Schallert went to ×îÐÂÐÓ°ÉÔ´´ and returned by bus with a bag of cash.

John Klipfel rented 40 acres of farmland from Schallert, sharing expenses and profits with her. He said she'd call at 4:30 a.m. to discuss a contract. She was so tight with money that letters were always written on the back of something else.

When she did work on her farmland, she often slept in barn lofts. When she stayed at her home in Portageville, she'd cross the street to use the bathroom at St. Eustachius Catholic Church, where she often slept in the choir loft.

"She lived a different life all together," Klipfel, a pallbearer at her funeral, said. But, he added, "She was awful nice to us and done wonderful things for the church and things."

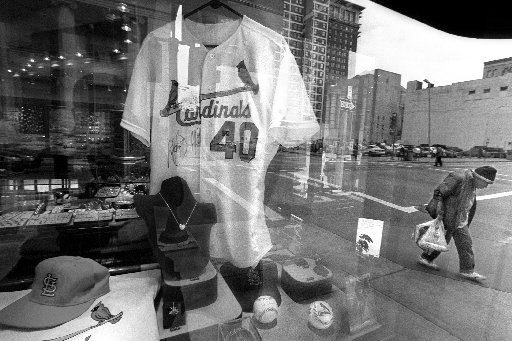

In 2000, a Post-Dispatch photo of a downtown boutique included an unidentified woman in the background. She held bags in one hand as she shuffled past the store, hunched over and wearing a winter cap and jeans. Circuit court clerks immediately recognized it was Schallert.

DISPERSING HER MONEYÌý

In her later years, Schallert often disappeared for months without checking in with family, said her brother Bernard.

She was once beaten up in an alley, suffering bruises and cuts to her face, said Arlene Weiss, a neighbor at the Louisiana Avenue home.

Weiss said Schallert would not let people inside the home and rarely let anyone help her. A few months before she died of lung cancer, a handyman discovered Schallert on her kitchen floor and broke in to help, Weiss said.

Her death in 2004 opened the doors she locked herself behind, revealing homes stuffed like closets.

The house on Milentz, valued at $60,000, needed $30,000 in repairs, according to court records. Boxes filled with papers, old clothing and even uncashed checks and money orders were piled nearly to the ceiling. Several Dumpsters were filled with everything from an arsenal of canned preserves to a broken go-kart that a neighbor said his family threw out in the 1960s.

In all, Schallert left behind at least two houses in ×îÐÂÐÓ°ÉÔ´´, three in Portageville and several small farms.

She was just as much of a financial pack rat, with some $750,000 scattered across bank accounts, safety deposit boxes — one holding an empty medicine bottle — and stakes in a cotton gin.

She deeded 400 acres of farmland to relatives, nuns in Clyde, Mo., and her church in Portageville, which also received an endowment of $200,000. Rents and interest pay for scholarships at the church grade school and daily operations.

Schallert had banged out her will on a typewriter. Clause No. 7 stipulated that 75 percent of her money be used to start a women's home, where residents could be safe and "have all the bread and water they wanted to eat free of charge."

Schallert didn't have enough to fulfill her wish, a court found. The handler of her estate was put in touch with Lydia's House. An attorney for Gateway Homeless heard about the case. Attorneys for both charities petitioned the court, arguing their clients best fulfilled Schallert's wishes. Probate Judge David Dowd agreed.

They received the money in 2008. Today, both organizations continue to lean on the funds.

Just last week, part of Schallert's gift helped spruce up one of 35 apartments provided by Lydia's House around ×îÐÂÐÓ°ÉÔ´´ for victims of domestic violence. The new tenant will have a free home for two years, access to a library, a community kitchen and space where she can recover with people carrying similar tragedies.

It's unclear why Schallert wanted to leave so much of her nest egg for a shelter.

Maybe she felt too many women were "unprotected and neglected," said Bernard Schallert.

Or maybe, he said, "it was because she was a bag lady."